Integrase Inhibitor: Key Insights and Treatment Options

When working with Integrase Inhibitor, a class of antiretroviral drugs that block the HIV integrase enzyme, preventing viral DNA from integrating into host cells. Also known as INSTI, it has become a cornerstone in modern HIV care.

The target of these drugs is the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS and relies on integrase to insert its genetic material into human DNA. By stopping that step, integrase inhibitors halt the chain of events that lead to full‑blown infection.

Integrase inhibitors are a vital component of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), the combination of medicines used to treat HIV infection. ART blends drugs from different classes so the virus faces multiple roadblocks at once, and the addition of an integrase inhibitor gives the regimen extra punching power.

To understand why, think about Viral Replication, the process by which viruses make copies of themselves inside host cells. HIV first converts its RNA into DNA, then uses integrase to weave that DNA into the host genome. Once integrated, the virus can hijack the cell’s machinery forever. Blocking integration cuts the replication cycle short, keeping the viral load low.

One challenge that keeps clinicians on their toes is Drug Resistance, the ability of HIV to mutate and evade the effects of medications. Resistance can develop if the virus isn’t fully suppressed, so doctors often pair an integrase inhibitor with two other agents to create a high barrier against mutation.

Today’s market offers several FDA‑approved integrase inhibitors: raltegravir, elvitegravir, dolutegravir, and bictegravir. Each has its own dosing schedule, pill burden, and interaction profile, but all share the core benefit of rapid viral load reduction. Dolutegravir and bictegravir, for example, are favored for their once‑daily dosing and high resistance barrier.

Compared with older classes—like reverse transcriptase inhibitors or protease inhibitors—integrase inhibitors tend to have fewer metabolic side effects and a cleaner drug‑interaction profile. That makes them especially attractive for patients who are on multiple medications or who have cardiovascular risk factors.

Guidelines from the WHO and major HIV societies now recommend starting most treatment‑naïve patients on an integrase‑based regimen. The reasoning is simple: faster viral suppression, lower chances of resistance, and better tolerability translate into higher long‑term success rates.

Side effects are generally mild, with headache and occasional nausea being the most reported. Rarely, patients may experience increases in serum creatinine due to inhibition of tubular secretion—not true kidney damage, but something clinicians monitor during routine labs.

Research is still pushing the envelope. Long‑acting injectables that combine an integrase inhibitor with a reverse transcriptase inhibitor are in late‑stage trials, promising monthly or even quarterly dosing. Studies also explore using integrase inhibitors as pre‑exposure prophylaxis for high‑risk groups.

When choosing an integrase inhibitor, doctors weigh factors like patient age, co‑existing conditions, potential drug interactions, and the likelihood of adherence. For pregnant patients, dolutegravir is now preferred after early‑pregnancy safety data cleared concerns.

Below you’ll find a curated list of articles that dive deeper into specific integrase inhibitors, compare them with other drug classes, discuss resistance patterns, and offer practical tips for clinicians and patients alike. Explore the collection to get a full picture of how these drugs are shaping modern HIV therapy.

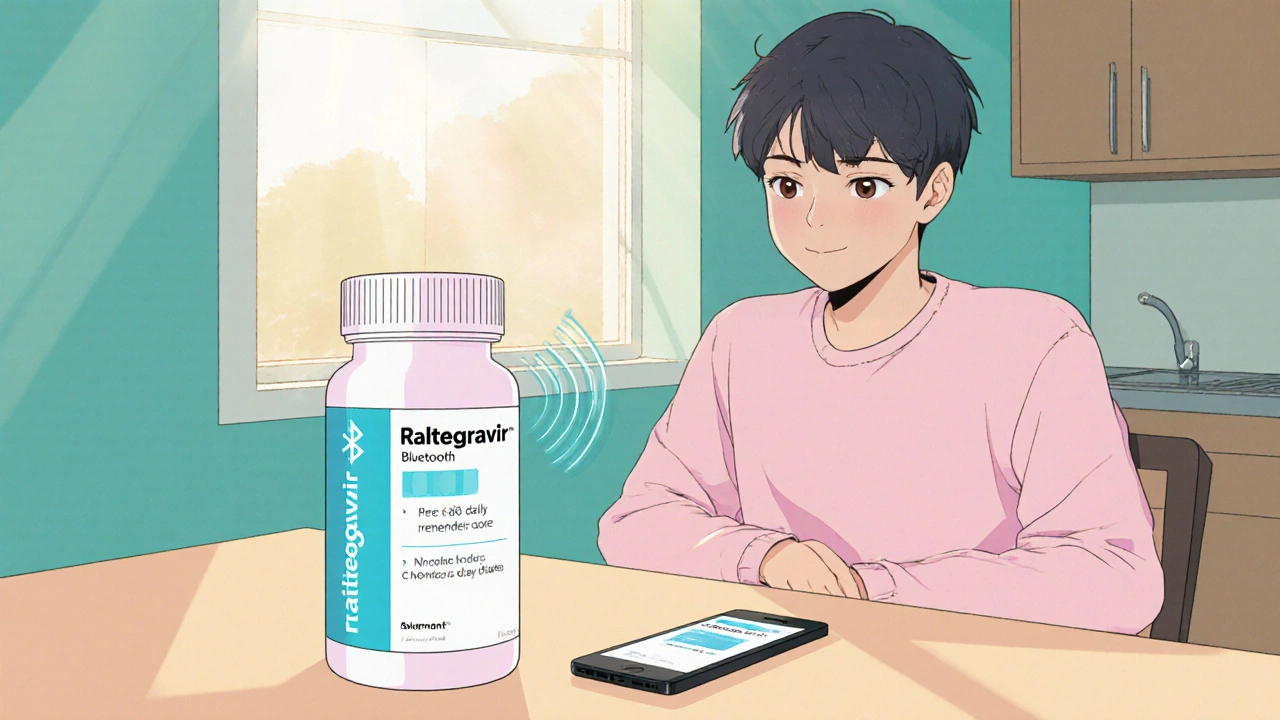

Raltegravir: How Technology Enhances HIV Treatment & Management

- Date: 22 Oct 2025

- Categories:

- Author: David Griffiths

Explore how Raltegravir works, its role in HIV therapy, and how digital tools, telemedicine, and AI improve adherence and outcomes.