When a drug goes directly into your bloodstream - through an IV, injection, or implant - there’s no safety net. Your skin, stomach acid, or immune system won’t filter out contaminants. That’s why sterile manufacturing for injectables isn’t just about cleanliness. It’s about survival. A single bacterium in a vial can trigger sepsis. A single endotoxin molecule can cause organ failure. And history has shown us what happens when this fails: the 2012 meningitis outbreak linked to contaminated steroid injections killed 64 people and sickened 751. That’s not a statistic. That’s real people. And it happened because someone skipped a step.

Why Sterile Manufacturing Is Non-Negotiable

Oral pills pass through your digestive system. Your body has defenses there. Injectables don’t. They go straight into blood or tissue. That’s why the standard for sterility is extreme: a contamination probability of less than one in a million (SAL 10-6). This isn’t arbitrary. It’s based on decades of failures and deaths. The 1955 Cutter Laboratories polio vaccine disaster, where incomplete inactivation led to paralysis and death, forced the first real GMP rules. Since then, every major outbreak has led to tighter standards. The World Health Organization, the FDA, and the EU all agree: if you’re making something to be injected, you must operate under conditions that make microbial contamination nearly impossible. That means more than just wearing gloves. It means controlling every variable - air, water, surfaces, people, even the way someone moves.Two Paths to Sterility: Terminal vs. Aseptic

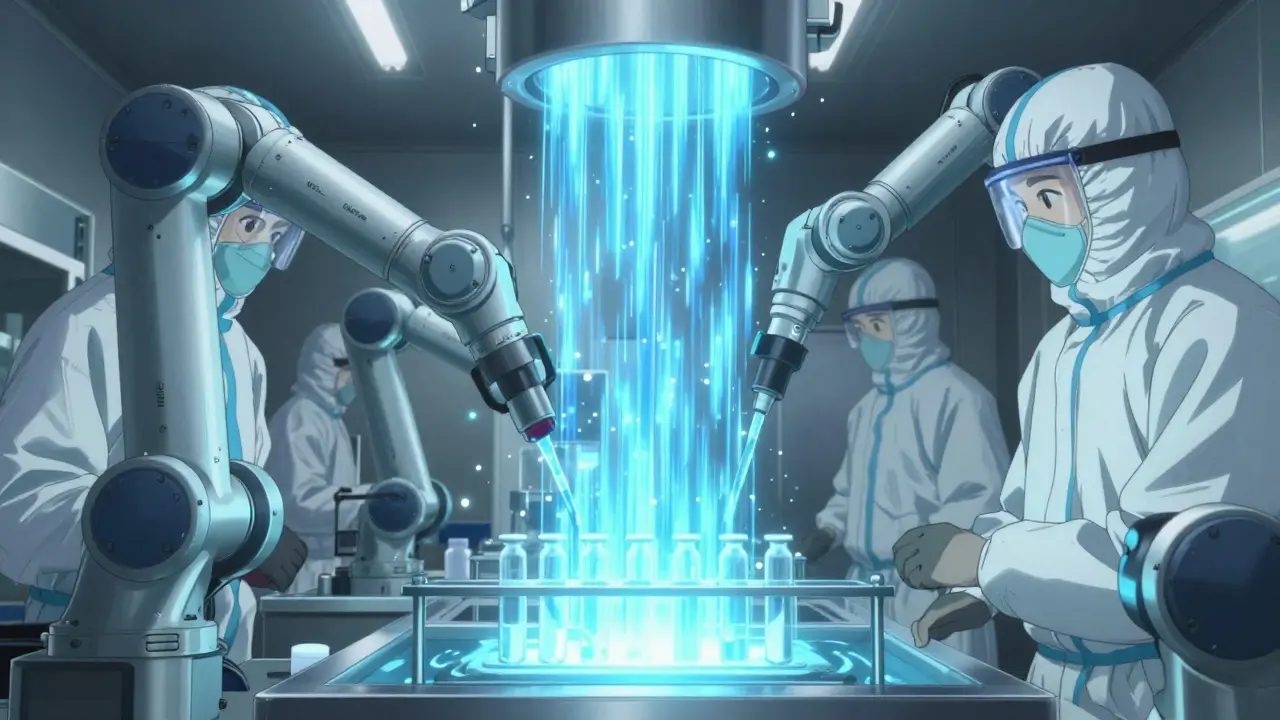

There are only two ways to make a sterile injectable: terminal sterilization or aseptic processing. You pick one based on what the drug can survive. Terminal sterilization means you make the product, seal it in its container, then kill everything inside with heat or radiation. Steam at 121°C for 15-20 minutes is the gold standard. It’s reliable. It gives you a sterility assurance level of 10-12 - better than the required 10-6. But here’s the catch: only 30-40% of injectables can handle this. Biologics like monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, or protein-based drugs? They fall apart under heat. So they can’t go through terminal sterilization. That’s where aseptic processing comes in. This is where the real engineering and human discipline kick in. Everything - the vials, stoppers, solutions, equipment - is sterilized separately. Then, in a sealed, ultra-clean room, the drug is filled into containers without ever being exposed to unsterile air. This happens in an ISO 5 environment (Class 100), where no more than 3,520 particles larger than 0.5 micrometers are allowed per cubic meter of air. That’s like having less than one grain of sand in a small shoebox - but for airborne particles.The Cleanroom: Your Invisible Shield

Aseptic processing doesn’t happen in a regular lab. It happens in a cleanroom - a room designed like a fortress against contamination. These rooms are built in layers. You start in an ISO 8 area (like a hospital corridor) to put on your gown. Then you move to ISO 7, then ISO 6, and finally enter the ISO 5 filling zone. Each step has stricter controls. Airflow matters. In the ISO 5 zone, air moves in one direction - downward, like a silent waterfall - at 0.3 to 0.5 meters per second. This pushes particles away from the product. The air is changed 20 to 60 times every hour. Temperature and humidity are locked at 20-24°C and 45-55% RH. Too dry? Static builds up and attracts dust. Too humid? Mold grows. Pressure is critical too. Each room is kept at a higher pressure than the one before it. That way, if a door opens, clean air flows out - not dirty air in. The difference? 10-15 Pascals. That’s less than the pressure of a gentle breath. But it’s enough to keep contamination out.Water, Containers, and the Hidden Enemy: Endotoxins

You can’t just use tap water. You need Water for Injection (WFI). It’s distilled, filtered, and treated to remove everything - including pyrogens, which are toxic fragments from dead bacteria. Even if the drug is sterile, if it has endotoxins, it can still make someone sick. USP <85> requires WFI to have less than 0.25 EU/mL. That’s tiny. To destroy those endotoxins, glass vials and stoppers are heated to 250°C for at least 30 minutes. That’s hotter than a home oven. And it’s not optional. It’s required by FDA guidance. Containers must also pass a leak test. If a vial has a microscopic crack, bacteria can get in later. The test? Helium leak detection at 10-6 mbar·L/s. That’s like detecting a pinhole in a balloon from 100 meters away.

People Are the Biggest Risk

No matter how good the machines are, people are the most common source of contamination. A person sheds 100,000 skin flakes per minute. That’s why staff in sterile areas wear full gowns, masks, hoods, and double gloves. They train for 40-80 hours just to learn how to move without stirring up air. They practice every six months in a media fill test - filling fake product with growth media to see if anything grows. If more than 0.1% of the vials show contamination, the whole process is shut down until they fix it. A manager from a top pharma company reported three media fill failures in one quarter - each costing $450,000. Why? A glove tore during a transfer. That’s it. One tiny tear. One missed check. One failed batch.Technology: Isolators vs. RABS

Two systems dominate modern sterile filling: RABS (Restricted Access Barrier Systems) and isolators. Both create a physical barrier between the operator and the product. But they work differently. RABS are like high-tech gloveboxes with transparent walls. Operators reach in through gloves to handle equipment. They’re cheaper and easier to use. But they still allow some human interaction. Isolators are fully sealed. Everything is transferred in through airlocks or sterilized by UV or hydrogen peroxide. Operators control everything from outside using robotic arms. They reduce contamination risk by 100 to 1,000 times, according to experts. But they cost 40% more to install and maintain. The Parenteral Drug Association says properly run RABS can match isolators. But the data from 2023 shows isolators are becoming the norm in new facilities. Why? Because the margin for error is zero.Costs and the Business of Sterility

Sterile manufacturing isn’t cheap. A small-scale facility (5,000-10,000 L/year capacity) costs $50-100 million to build. A single batch of aseptic processing? $120,000 to $150,000. Terminal sterilization? Around $50,000. But the real cost isn’t in the numbers - it’s in the risk. A single sterility failure can cost $1.2 million on average. That’s not just lost product. It’s lost time, regulatory scrutiny, damaged reputation, and sometimes lawsuits. In 2023, 68% of sterile manufacturing facilities had at least one sterility test failure. That’s nearly every other company. The market is growing fast. Sterile injectables hit $225 billion in 2023. Biologics - drugs made from living cells - are driving most of that growth. They’re complex, fragile, and almost always require aseptic processing. That’s why more than 40% of new drug approvals are sterile injectables.

Regulatory Pressure Is Rising

The EU updated its GMP Annex 1 in 2022. It now demands continuous environmental monitoring - not just daily checks. That means particle and microbial sensors running 24/7. The FDA followed with new guidance in 2023, pushing for digital tools, AI, and real-time data. Inspections are getting tougher. In 2022, the FDA issued 1,872 citations for sterile manufacturing issues - up from 1,245 in 2019. The biggest problems? Inadequate environmental monitoring (37% of citations), media fill failures (28%), and poor staff training (22%). These aren’t high-tech failures. They’re human ones.What’s Next?

The future of sterile manufacturing is automation, digital twins, and rapid testing. Robotic filling systems are growing fast. Companies are replacing manual inspection with AI-powered cameras that catch defects at 0.05% - down from 0.2%. Rapid microbiological methods are cutting test times from 14 days to 24 hours. That means faster releases and less inventory tied up. But the core hasn’t changed. Sterile manufacturing still comes down to one thing: discipline. Every step. Every person. Every day. Because when you’re making something that goes straight into the blood, there’s no room for shortcuts. Not one.Final Thought

You don’t need to be a scientist to understand this: if a drug is injected, it must be clean. Not mostly clean. Not usually clean. Sterile. And that’s not just regulation. It’s ethics. Every vial, every syringe, every dose - it carries someone’s life. The standards exist because people died. And they keep evolving because we haven’t stopped learning.What is the difference between terminal sterilization and aseptic processing?

Terminal sterilization kills microbes after the product is sealed, using heat or radiation. It’s reliable but only works for products that can survive high temperatures, like saline solutions. Aseptic processing keeps everything sterile during manufacturing without applying heat to the final product. It’s used for fragile drugs like biologics but requires extreme control over air, personnel, and equipment.

Why are cleanrooms classified by ISO levels?

ISO classifications define how clean the air is based on particle count. ISO 8 is the least clean (used for gowning), while ISO 5 is the cleanest (used for filling). Each level has strict limits on how many particles of a certain size are allowed per cubic meter. This system ensures that contamination risk decreases as you get closer to the product.

What happens if a sterile injectable fails a sterility test?

The entire batch is destroyed. Regulatory agencies are notified. The company must investigate why it failed - often tracing it to a breach in gowning, equipment, or environmental monitoring. Repeated failures can trigger FDA inspections, fines, or even facility shutdowns. The average cost per failure is $1.2 million.

Are all injectables required to be sterile?

Yes - if they’re administered directly into the bloodstream, spinal fluid, or sterile tissues. That includes IV bags, intramuscular shots, eye injections, and implants. Oral or topical products don’t need the same level of sterility because the body has natural barriers.

How often do sterile manufacturing facilities fail inspections?

In 2022, 68% of sterile manufacturing deficiencies cited by the FDA were related to aseptic technique failures. Environmental monitoring issues were the most common, followed by media fill failures and staff training gaps. Nearly 70% of facilities had at least one sterility test failure in 2022.

So if a vial has one bad particle, someone could die? That’s wild. I never thought about how much goes into just one shot.

Guess I take meds for granted.