Pediatric Dose Safety Calculator

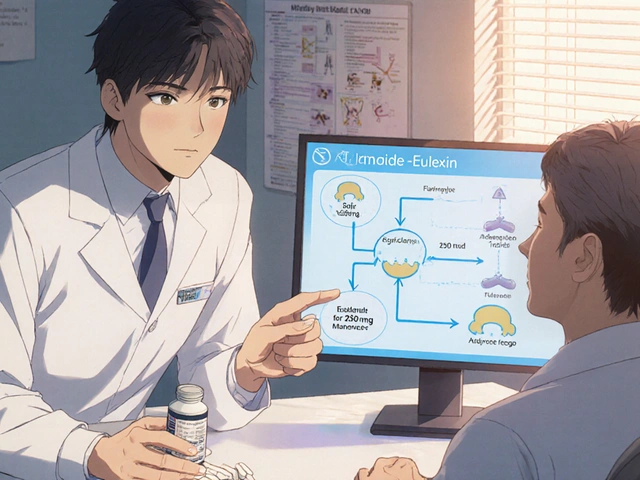

This tool estimates safe medication dosing ranges for children based on weight and age. Pediatric safety networks like CPCCRN track these dosing patterns to detect rare side effects that single hospitals might miss.

Results

When a child is given a new medication or enters a critical care unit, doctors don’t just hope it works-they need to know what might go wrong. But tracking side effects in kids isn’t like tracking them in adults. Children aren’t small adults. Their bodies change rapidly. Doses must be calculated precisely. And many drugs simply weren’t tested on them. That’s where pediatric safety networks come in. These aren’t just research groups. They’re coordinated systems that connect hospitals, states, and data experts to catch side effects most studies miss.

Why Traditional Studies Fail Kids

Most drug trials happen in adults first. Then, if a drug works, it gets used in children-sometimes years later, without proper safety data. This gap isn’t just a delay. It’s dangerous. A 2013 study in Academic Pediatrics found that over 70% of medications used in pediatric intensive care units had never been formally tested in kids. That means doctors were guessing at doses, watching for reactions, and often only noticing problems after a child got sick. Traditional randomized trials can’t always answer these questions. For rare side effects, you need hundreds or thousands of patients. No single hospital sees enough kids to spot a pattern. And some side effects only show up after weeks or months-too long for a short-term trial. That’s why researchers built networks: to pool data across dozens of sites and find what no one clinic could see alone.The CPCCRN: A Network Built for Critical Care

One of the most structured efforts was the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN), launched by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in 2014. It wasn’t a loose collaboration. It was a tightly governed system with seven major children’s hospitals, one central data hub, and strict rules. Each hospital had to prove it could enroll patients, collect data accurately, and follow protocols. The Data Coordinating Center didn’t just store numbers-it designed the tools. Standardized forms for recording every reaction. Automated alerts for unexpected drops in blood pressure or liver enzyme spikes. Statistical models to calculate how many kids were needed to detect a rare side effect. One site lead later said, "Without the DCC’s sample size calculations, we would’ve run studies too small to find anything meaningful." But the real power was in the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. This group, made up of independent doctors and statisticians, reviewed every adverse event in real time. If a pattern emerged-say, three kids across different hospitals developed the same rare skin rash after a new antibiotic-the board could pause the study and alert everyone. That kind of speed is impossible in a single hospital.Child Safety CoIIN: Preventing Harm Before It Happens

While CPCCRN focused on hospital treatments, the Child Safety Collaborative Innovation and Improvement Network (CoIIN) worked outside the clinic. Funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), it targeted injuries-falls, car crashes, poisonings, even violence. Its goal wasn’t just to track side effects of medicine, but to prevent harm from everyday risks. CoIIN didn’t run drug trials. It ran change experiments. A state health department might try a new program to teach teens about dating violence. They’d use worksheets and real-time dashboards to track how many kids reported feeling safer. But they also looked for unintended consequences. One program noticed that after increasing focus on sexual violence in school sessions, some students became overly fearful of normal social interactions. The team adjusted their materials-shifting from fear-based messaging to empowerment-based ones. Unlike CPCCRN, CoIIN didn’t have centralized medical records. It relied on state-level reporting. That meant less precision in medical data, but more flexibility in policy. While CPCCRN caught drug reactions, CoIIN caught systemic flaws in how safety programs were delivered.

It’s not just about drugs-it’s about how we treat children as passive subjects in a system built for adults. We’ve been treating pediatric care like a scaled-down version of adult medicine, and that’s not just lazy, it’s lethal. The body doesn’t just shrink-it reconfigures. Metabolism, organ maturation, blood-brain barrier permeability-they’re not linear functions. You can’t extrapolate from a 70kg man to a 7kg infant and call it science. These networks are the first real attempt to stop guessing and start observing. And yet, we still fund them like they’re temporary experiments, not foundational infrastructure.