Why do some people struggle to lose weight even when they eat less and exercise more? It’s not laziness. It’s not willpower. It’s biology. Obesity isn’t just about eating too much-it’s a deep, broken system inside your body that’s been rewired by years of excess calories, hormones, and inflammation. The science behind it is complex, but the core problem is simple: your brain and body have lost the ability to regulate hunger, fullness, and energy use properly.

How Your Brain Controls Hunger (And Why It Fails)

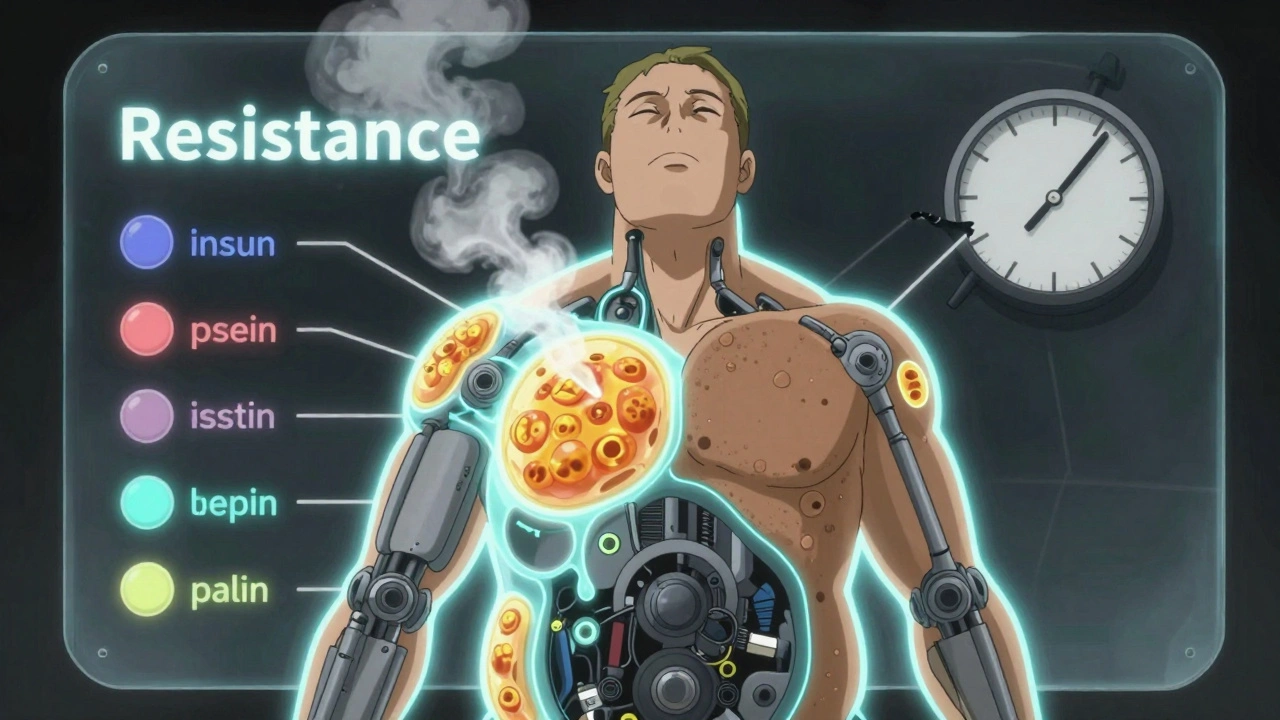

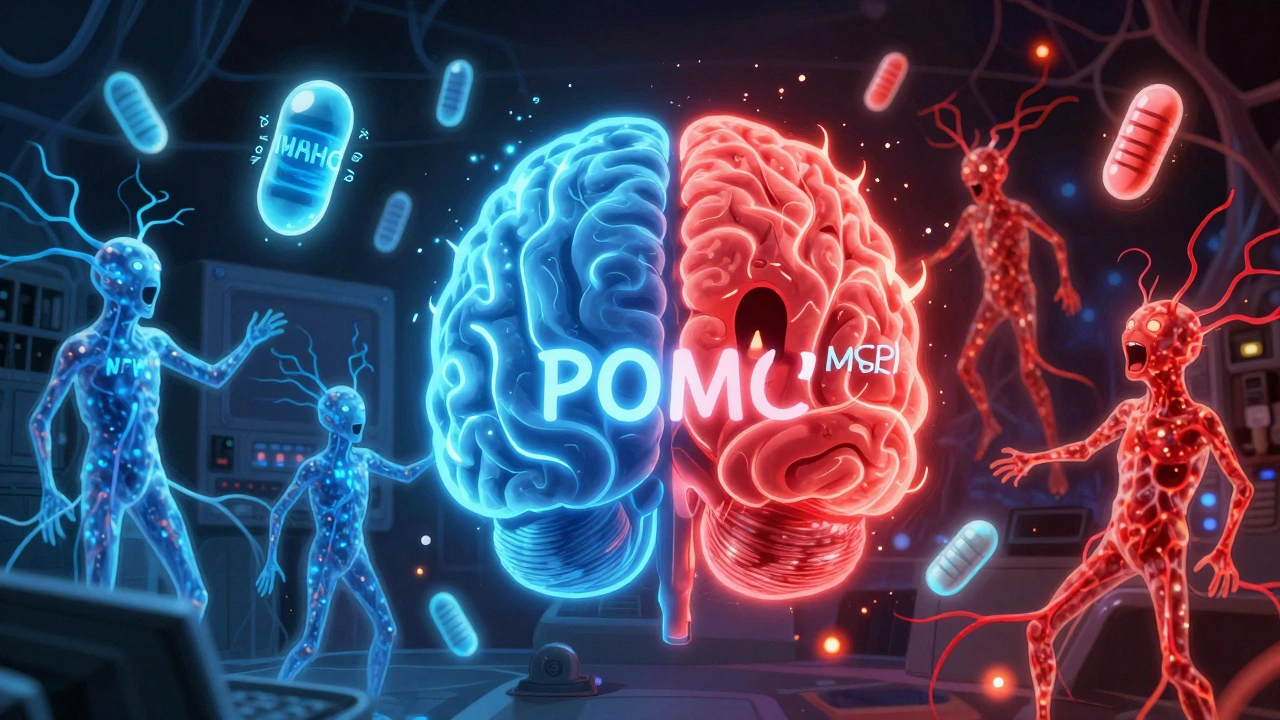

At the center of this mess is a tiny region in your brain called the arcuate nucleus. It’s like the control room for your appetite. Two groups of neurons here fight for control: one tells you to stop eating, the other screams for more food. The "stop eating" team is made up of POMC neurons. When they fire, they release alpha-MSH, a chemical that tells your brain you’re full. In lab studies, activating these neurons cuts food intake by up to 40%. The other team-NPY and AgRP neurons-does the opposite. When they’re active, you feel ravenous. In mice, turning on just these neurons makes them eat 3 to 5 times more than normal in minutes. These neurons don’t work alone. They listen to signals from your fat, gut, and pancreas. Leptin, a hormone made by fat cells, is supposed to calm the hungry neurons and boost the fullness ones. In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, those numbers jump to 30-60 ng/mL. But here’s the catch: your brain stops listening. That’s called leptin resistance. It’s not that you don’t have enough leptin-it’s that your brain ignores it. And that’s the main reason most diets fail. Insulin plays a similar role. After you eat, insulin rises from 5-15 μU/mL to 50-100 μU/mL, telling your brain to reduce hunger. But in people with insulin resistance, that signal gets drowned out. Ghrelin, the hunger hormone, spikes before meals-normally from 100-200 pg/mL to 800-1000 pg/mL. In obesity, ghrelin doesn’t drop after eating like it should, so you never feel satisfied.The Metabolic Slowdown You Can’t See

Your body doesn’t just overeat-it also burns less energy. That’s metabolic dysfunction. When you gain weight, your fat tissue doesn’t just grow larger; it becomes inflamed and starts releasing chemicals that disrupt how your body uses energy. One key player is the PI3K/AKT pathway. This is the main route leptin and insulin use to signal fullness. When you eat a high-fat diet for weeks, this pathway gets blocked. Studies show that if you block PI3K in the brain, leptin loses its power to suppress appetite. That’s why even high doses of leptin don’t help most obese people-it’s like shouting into a wall. Then there’s mTOR, a system that senses nutrients. When it’s turned on, it tells your body you’ve had enough. In aging mice, stimulating mTOR reduces weight gain by 25%. But in obesity, this system gets sluggish. Your body stops sensing when it’s full, even when you’ve eaten enough. Brown fat, the kind that burns calories to make heat, also goes quiet. In lean people, it’s active. In obesity, it shuts down. One study showed that blocking PTEN-a protein that turns off PI3K-boosted brown fat activity and cut body weight by 15-20% in mice. But in humans, this system is suppressed by years of overeating and inactivity.

The leptin resistance mechanism is so underdiscussed in mainstream health media. People think it’s just ‘eat less, move more’ but the neuroendocrine feedback loops are fucking broken at a cellular level. I’ve seen patients on 1200-calorie diets still gaining weight because their hypothalamus is deaf to satiety signals. It’s not laziness-it’s a neurochemical blackout.

And the PI3K/AKT pathway blockade? That’s why GLP-1 agonists work better than keto or intermittent fasting for most. They bypass the broken circuit entirely. The fact that pharma spent 30 years chasing leptin supplements instead of downstream targets is criminal.

Also, brown fat suppression isn’t just from inactivity-it’s from chronic hyperinsulinemia. Cold exposure studies show you can reactivate it, but only if you fix the insulin first. No amount of spin bike classes fixes that.

Why do we still treat obesity like a behavioral issue when the science’s been clear since 2015? We’re literally blaming people for having a neurological disorder.

Setmelanotide isn’t a miracle drug-it’s the first real proof that this is a brain wiring problem. We need to reframe the entire public health narrative. Not ‘lose weight,’ but ‘restore regulatory function.’