Dietary Fiber is a plant‑based carbohydrate that the human small intestine cannot fully break down, providing bulk, fermentable substrate, and a range of metabolic benefits. When you eat enough fiber, the gut moves more smoothly, blood sugar stays steadier, and the tiny microbes living in your colon thrive. All of those effects team up to stop the body from missing out on the nutrients packed into your meals.

Why Poor Absorption Happens

Before we dig into fiber’s role, it helps to know the usual culprits behind weak nutrient uptake. Digestion is a complex cascade of mechanical and chemical processes that break food into absorbable molecules. If any step stalls-slow stomach emptying, rapid intestinal transit, or an imbalanced gut lining-nutrients slip through the cracks.

Nutrient Absorption is a process by which the small intestine transports vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients into the bloodstream. Factors like low enzyme activity, damaged villi, or an over‑fast passage through the intestines can leave meals only half‑digested, turning a nutritious plate into waste.

Enter the unsung hero: fiber. By modulating the speed of intestinal content, feeding beneficial microbes, and forming a protective gel, fiber tackles each of those pitfalls head‑on.

How Fiber Works: The Core Mechanisms

Fiber’s magic lies in three interlinked actions:

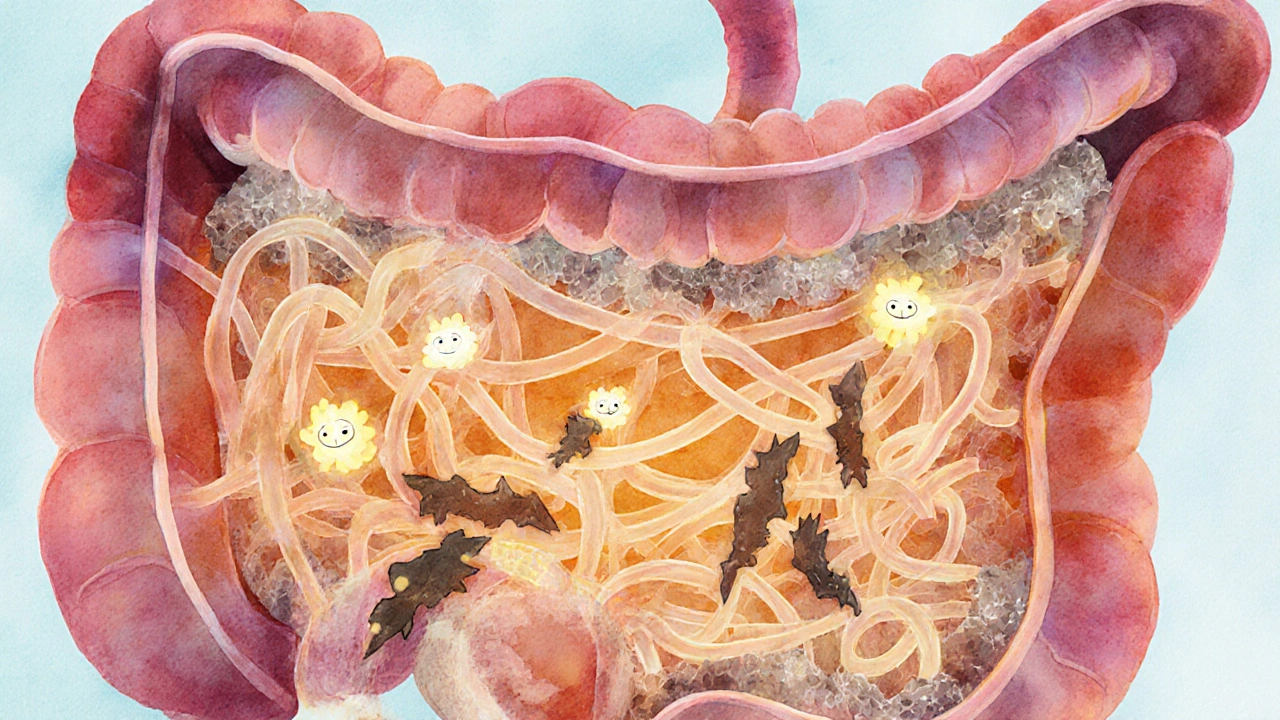

- Bulking and Mechanical Stimulation: Insoluble fiber adds bulk, stimulating the Gut Microbiota is a community of trillions of bacteria, archaea, and fungi living in the colon and the muscular walls of the intestine. The resulting gentle contractions-known as peristalsis-slow down transit enough for enzymes to work.

- Fermentation and Short‑Chain Fatty Acid Production: Soluble fiber reaches the colon intact, where Short‑Chain Fatty Acids are a group of metabolites (acetate, propionate, butyrate) produced by microbial fermentation of fiber are generated. These acids feed colon cells, tighten the gut barrier, and signal the body to release hormones that regulate appetite and glucose.

- Glycemic Modulation: The gel formed by soluble fiber traps sugars, flattening the post‑meal spike in blood glucose. A steadier glucose curve means the intestine’s transporters stay active longer, improving overall nutrient uptake.

In short, fiber creates the perfect environment for efficient digestion while protecting the gut from inflammation-a win‑win for absorption.

Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber: A Quick Comparison

| Attribute | Soluble Fiber | Insoluble Fiber |

|---|---|---|

| Water Solubility | Forms viscous gel in water | Retains shape, does not dissolve |

| Primary Effect | Slows glucose absorption, feeds gut bacteria | Increases stool bulk, accelerates transit |

| Typical Sources | Oats, beans, apples, psyllium | Whole wheat, nuts, cauliflower, skins |

| Impact on Glycemic Index | Lowers GI of meals | Minimal direct effect |

| Fermentation Yield | High SCFA production | Low SCFA production |

Both types are essential. A diet rich in mixed fiber ensures you get the gel‑forming benefits of soluble fiber and the mechanical cleaning power of insoluble fiber.

Fiber’s Direct Influence on Nutrient Absorption

When the gut moves too fast, nutrients have less contact time with the lining, leading to “poor absorption.” Insoluble fiber’s bulk nudges the intestine to move at a measured pace, extending that contact window. Meanwhile, soluble fiber’s fermentation products-especially butyrate-strengthen the tight junctions between epithelial cells, preventing leakage and supporting active transport mechanisms.

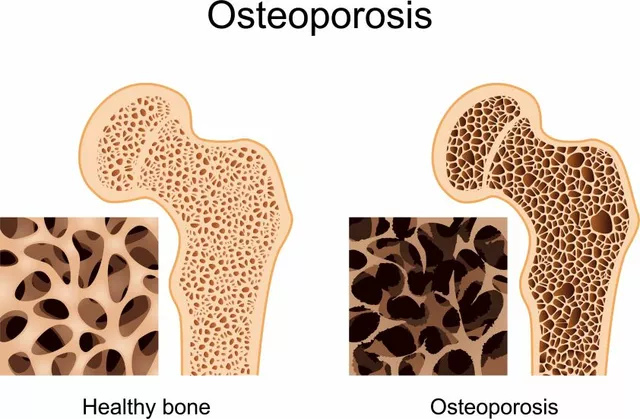

Research from the Nutrition Society (2023) showed that participants who added 15g of mixed fiber to a standard meal increased iron and calcium uptake by roughly 12% compared with a low‑fiber control. The same study noted a 20% reduction in post‑prandial triglyceride spikes, aligning with the idea that fiber slows lipid emulsification and absorption, giving the body a chance to process fats more efficiently.

Beyond minerals, fiber also helps vitamins. Fat‑soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) benefit from slower intestinal transit, which gives micelle formation more time. Water‑soluble vitamins (C, B‑complex) are protected from rapid fermentation that can otherwise degrade them.

Practical Ways to Boost Your Fiber Intake

- Start meals with a salad that includes raw carrots, cucumber skins, and a sprinkle of seeds-these add insoluble crunch.

- Swap white rice for brown rice or quinoa; both provide a blend of soluble and insoluble fiber.

- Mix a spoonful of Psyllium is a water‑absorbing soluble fiber source that forms a thick gel into smoothies for an extra gel‑forming boost.

- Include legumes (lentils, chickpeas) in soups or stews at least three times a week.

- Snack on fresh fruit with the skin on-apples, pears, and berries are perfect.

Aim for 25g per day for women and 38g for men, as recommended by the Australian Dietary Guidelines. If you’re new to high‑fiber meals, increase gradually to avoid gas and bloating.

Related Concepts: Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Glycemic Control

Fiber often gets grouped with Prebiotics are a type of soluble fiber that selectively feeds beneficial gut bacteria. While all soluble fiber has prebiotic potential, inulin and fructooligosaccharides are the most studied. Pairing prebiotics with Probiotics are live microbial supplements that colonize the gut can amplify SCFA production, further tightening the gut barrier and enhancing absorption.

The Glycemic Index is a ranking of carbohydrates based on how quickly they raise blood glucose levels drops noticeably when meals contain soluble fiber. A lower GI helps insulin work efficiently, which indirectly supports the active transport of many nutrients.

If you’re managing metabolic syndrome or type2 diabetes, weaving fiber into every bite can be a simple, drug‑free strategy to keep blood sugar-and nutrient uptake-in check.

Key Takeaways

- Fiber adds bulk and forms a gel, slowing intestinal transit and giving enzymes time to act.

- Soluble fiber feeds the gut microbiota, producing SCFAs that protect the gut lining.

- Insoluble fiber provides mechanical stimulation, preventing too‑fast passage of food.

- A mix of both types improves absorption of minerals, vitamins, and macronutrients.

- Practical diet tweaks-salads, whole grains, legumes, fruit with skin-can help you hit the daily fiber target.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can too much fiber hurt absorption?

Excessive fiber (over 50g daily) can bind minerals like calcium, iron, and zinc, making them harder to absorb. The key is balance-mix soluble and insoluble sources and spread intake throughout the day.

Is fiber the same as prebiotic?

All prebiotics are a type of soluble fiber, but not all soluble fiber has strong prebiotic effects. Inulin, fructooligosaccharides, and resistant starch are the most potent prebiotics.

How quickly does fiber improve absorption?

Gut microbiota respond within days, but measurable improvements in mineral absorption typically appear after 2‑4 weeks of consistent fiber intake.

What foods give the best mix of soluble and insoluble fiber?

Oats with a handful of nuts, a mixed salad with seeds, and a side of lentil soup provide both types in one meal.

Does cooking destroy fiber?

Heat does not break down fiber; it can actually make insoluble fiber more digestible by softening cell walls, while soluble fiber remains largely unchanged.

Can fiber help with specific deficiencies like iron?

Yes-by slowing transit, fiber allows more time for iron to bind to transport proteins, and the SCFAs produced improve the gut lining’s ability to absorb iron.

Should I take fiber supplements?

Supplements like psyllium can help reach daily goals, but whole foods also provide vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients that supplements lack.

Fiber functions as a physiochemical matrix that modifies transit velocity and enhances mucosal exposure to digestive enzymes. The resultant increase in residence time allows for optimal micelle formation and mineral chelation. Moreover the gel-like properties of soluble polysaccharides create a diffusion barrier that tempers postprandial glycemic spikes. This multimodal action underpins the observed improvements in nutrient bioavailability.