When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, you’d think a cheaper generic version would hit the shelves right away. But that’s not how it works. Behind every generic drug you pick up at the pharmacy is a legal battle that can last years - and the outcome can mean the difference between paying $5 or $500 for the same medicine. These aren’t just courtroom dramas. They’re decisions that directly affect how much you pay for insulin, blood pressure pills, or cancer treatments.

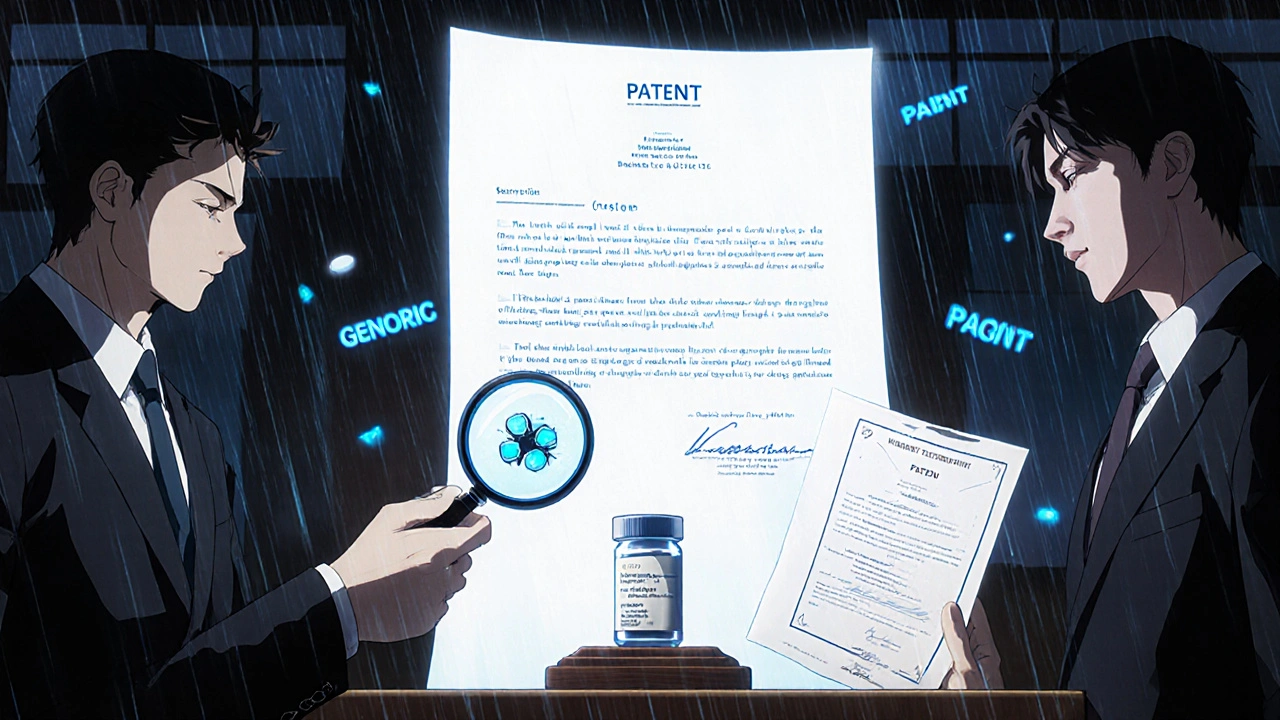

How Generic Drugs Break Patents - Legally

The system that lets generics enter the market is called the Hatch-Waxman Act. Passed in 1984, it was designed as a trade-off: give brand companies extra patent time to make up for the years they spent getting FDA approval, and give generics a clear path to challenge those patents. The key tool generics use is the Paragraph IV certification. When a generic company files for approval, they must state that the brand’s patent is either invalid or won’t be infringed. That’s a legal challenge - and it triggers a 30-month clock where the brand can sue to block the generic from launching.

It’s not just about filing paperwork. The generic has to prove the patent doesn’t hold up under the law. That’s where landmark court decisions come in. These aren’t abstract rulings. They change what kind of patents can even be enforced. One of the biggest shifts came in 2023 with Amgen v. Sanofi. Amgen held a patent covering millions of possible antibodies, but only showed how to make 26 of them. The Supreme Court said that’s not enough. You can’t claim ownership over something you haven’t actually invented or described in detail. This decision hit biologic drugs especially hard - the expensive, complex treatments for conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Suddenly, patents that looked bulletproof were vulnerable.

The Orange Book: The Hidden Rulebook

Every patent a brand company wants to protect is listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. It’s not a public database you can browse casually - it’s a legal document that determines whether a generic can even move forward. If a patent isn’t listed, the generic can’t be blocked. But here’s the problem: some companies list patents that have nothing to do with the actual drug. Maybe it’s a packaging patent, or a method of use that’s not even approved by the FDA. That’s called “evergreening.”

In 2024, the FDA proposed new rules to crack down on this. They want companies to prove every listed patent is directly tied to the drug’s approval. If they don’t, the patent won’t trigger a 30-month delay. This is a big deal. A 2024 study found that 38% of Orange Book listings were for patents that didn’t cover the drug’s active ingredient. That’s not innovation - it’s a delay tactic. And it’s costing patients billions.

When a Generic Wins - And When It Doesn’t

Not every challenge succeeds. In Allergan v. Teva (2024), the Federal Circuit ruled that a patent filed later can still block a generic if it’s the first one listed in the Orange Book. That might sound backwards - why would a later patent matter more? Because the system rewards the first company to file a challenge with 180 days of exclusive market access. If that company files a weak patent, but it’s the first one listed, they can still hold up everyone else. This decision gave brand companies a new tool: file a narrow, low-quality patent early, and use it to lock out competitors - even if a better patent comes later.

Then there’s Amarin v. Hikma. Hikma made a generic version of Amarin’s heart drug. But Hikma’s marketing materials suggested the drug could be used for off-label purposes - uses not approved by the FDA. Amarin sued, claiming this was “induced infringement.” The court agreed. It’s not enough to just make the drug. If your packaging or ads suggest uses the brand didn’t approve, you’re opening yourself up to a lawsuit. This has forced generic companies to be hyper-careful with every word on their labels. One legal team told me they now have three lawyers review every piece of marketing material before it’s printed.

Why This Matters to You

These cases aren’t just for lawyers and drug companies. They’re about your wallet. When a generic hits the market, prices drop by 80% to 85% within a year, according to the FTC. That’s how a $1,200 monthly insulin dose becomes $180. But if a patent battle drags on for 22 months - like one Reddit user reported - you’re stuck paying the high price. The same user said they paid $8,400 out of pocket because the generic was delayed.

And it’s not just insulin. Cardiovascular drugs, cancer treatments, and even asthma inhalers like ProAir are caught in these battles. In 2023, over 2,100 new patent cases were filed under the Hatch-Waxman Act. That’s up 12.7% from the year before. Each case costs an average of $6.8 million. Those costs don’t vanish - they get passed on to insurers, and eventually, to patients.

The Rise of the Patent Killer: IPRs

There’s a new weapon in the generic company’s arsenal: Inter Partes Review (IPR). This is a process at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) where a generic can challenge a patent’s validity without going to federal court. It’s faster, cheaper, and more predictable. In 2023, 78.3% of generic challenges used IPRs. That’s up from just 22% in 2015. Why? Because federal court cases take an average of 28.7 months. IPRs often wrap up in under 18 months.

But it’s not a silver bullet. Brand companies have adapted. They now file multiple patents - some for the drug, some for the method, some for the delivery system - hoping at least one will survive. And some IPRs are overturned on appeal. Still, it’s changed the game. Now, a generic company doesn’t just file an ANDA. They file an ANDA and an IPR. It’s become standard practice.

What’s Next?

The Supreme Court recently denied a rehearing in Amgen v. Sanofi, meaning the stricter enablement standard stands. That’s a win for generics - but it’s also a warning to innovators. If you’re developing a new biologic, you can’t just say “this could work for millions.” You have to show how to make it. That means more time, more money, more risk.

Meanwhile, the FDA is pushing for more transparency in the Orange Book. If they succeed, we could see fewer frivolous patents blocking generics. But brand companies are fighting back. They’re lobbying for stronger patent term extensions and pushing for more international patent alignment.

The bottom line? The system is broken - but it’s not broken beyond repair. The courts are starting to push back on patent abuse. The FTC is watching. And patients are speaking up. If the current trends hold, we could see patent litigation duration drop by 22% by 2028. That means faster access to affordable drugs. But it’s not guaranteed. The next big decision - whether it’s from the Supreme Court, the FDA, or Congress - could go either way.

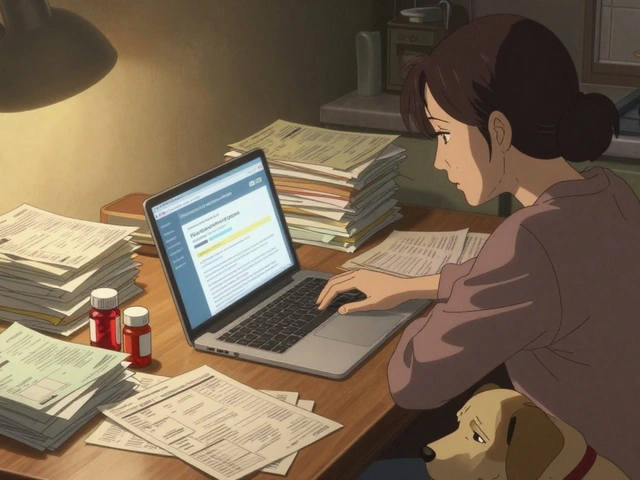

How to Know If a Generic Is Delayed - And What to Do

If you’re paying high prices for a drug that should have a generic, here’s what to check:

- Go to the FDA’s Orange Book website and search your drug. Look for any listed patents - especially those with recent filing dates.

- Check the generic manufacturer’s website. If they say “patent litigation pending,” that’s a red flag.

- Search for news about lawsuits involving your drug. Major cases often get covered by Bloomberg Law or FiercePharma.

- If you’re on Medicare or private insurance, ask your pharmacist: “Is there a patent dispute delaying the generic?” They often know before you do.

And if you’re paying out of pocket? Talk to your doctor. Sometimes, there’s a different drug in the same class that’s already generic. Or your insurer might offer a patient assistance program. Don’t assume you’re stuck with the high price - the system is complex, but there are often workarounds.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and why does it matter for generic drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a legal balance between brand-name drug companies and generic manufacturers. It lets generics challenge patents using Paragraph IV certifications and offers a 180-day exclusivity period to the first generic to file. In return, brand companies get extra patent time to make up for FDA approval delays. This system is why most prescriptions today are filled with generics - but it’s also why patent lawsuits are so common.

What is Paragraph IV certification?

Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement a generic drug company files when applying to the FDA. It says the brand’s patent is either invalid or won’t be infringed. This triggers a 30-month stay, during which the brand can sue to block the generic from launching. It’s the main legal tool generics use to enter the market early - and the trigger for most patent battles.

What is the Orange Book and how does it affect generic drug approval?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of all patents linked to approved brand-name drugs. If a patent is listed here, it can be used to block a generic from launching. Generic companies must check this list before filing. If a patent isn’t listed, it can’t be used in court. That’s why some brand companies list weak or irrelevant patents - to delay competition. The FDA is now cracking down on this practice.

How did Amgen v. Sanofi change patent law for biologics?

In Amgen v. Sanofi, the Supreme Court ruled that a patent can’t claim ownership over millions of possible molecules if the patent holder only shows how to make a few. This set a new standard for “enablement” - meaning you must fully describe how to make what you’re claiming. For biologics, which are complex protein-based drugs, this made many patents much harder to defend. It’s one of the biggest shifts in pharmaceutical patent law in decades.

What are IPRs and why are they important for generic companies?

IPR stands for Inter Partes Review. It’s a faster, cheaper process at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) where a generic company can challenge a patent’s validity without going to federal court. In 2023, nearly 80% of generic patent challenges used IPRs. They typically take under 18 months, compared to 28+ months in court. This has become a standard part of the generic drug entry strategy.

Why do some generic drugs take years to become available after a patent expires?

Even after a patent expires, generic entry can be delayed by lawsuits, complex patent listings, or strategic maneuvers by brand companies. A 30-month stay triggered by a Paragraph IV certification can delay a generic for two and a half years. Add in appeals, PTAB reviews, and patent thickets - multiple overlapping patents - and delays of 3 to 5 years are common. The FTC estimates over $127 billion in generic sales are being held up by these disputes through 2026.

Can a generic drug be blocked for promoting off-label uses?

Yes. In Amarin v. Hikma, a court ruled that even if a generic drug is chemically identical, marketing materials that suggest unapproved uses can be considered “induced infringement.” That means if your packaging or ads imply the drug can be used for conditions not approved by the FDA, you can be sued - even if you’re not making the drug for those uses. This has made generic companies extremely cautious about their marketing language.

What’s the impact of these patent battles on drug prices?

When a generic enters the market, prices typically drop by 80% to 85% within a year. But if patent litigation delays entry by even one year, patients pay millions more out of pocket. Studies show that unresolved patent disputes will delay $127 billion in generic sales through 2026. Cardiovascular and cancer drugs are most affected. The longer the battle, the longer people pay brand prices.

What to Watch For in 2025 and Beyond

The FDA’s proposed 2025 rule on Orange Book transparency could be the next turning point. If it passes, companies will need to prove every patent they list is directly tied to the drug’s approval. That could cut down on “patent thickets” and speed up generic entry.

Biosimilars - the generic version of biologic drugs - are also set to explode. Right now, they make up just 14% of generic patent cases. By 2027, that number could jump to 31%. These are even more complex than small-molecule generics. They’re harder to copy, harder to test, and harder to patent. The legal battles around them are just beginning.

One thing’s clear: the system is evolving. Courts are becoming more skeptical of broad patents. Regulators are pushing for transparency. And patients are demanding lower prices. The question isn’t whether these changes will happen - it’s how fast. And how much relief they’ll bring to the people who need affordable medicine the most.

This whole system is a joke. American pharma companies are robbing us blind while hiding behind legal loopholes. Canada gets these drugs for half the price, and we’re over here paying $500 for insulin like it’s gold. Time to nationalize drug pricing and stop letting lawyers dictate healthcare.