When you pick up a generic prescription, you expect it to be cheaper than the brand-name version. And for the most part, it is. But what you don’t see on the receipt is how wildly those prices can swing from one year to the next. Some generics drop in price by 80% after a new manufacturer enters the market. Others suddenly jump 300%, 500%, even over 1,000%. This isn’t random. It’s the result of a broken system where competition should be driving prices down-but often isn’t.

How Generic Drug Prices Usually Drop (When Competition Works)

When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic version typically costs about 90% of the original price. That’s already a big savings. But here’s where things get interesting: every new company that starts making the same drug pushes the price lower. By the time there are three generic makers, the price usually drops to about half of what the brand charged. With four or more competitors, it can fall to just 15% of the original cost.

This isn’t theory. The FDA tracked this pattern across hundreds of drugs. For example, generic versions of the blood pressure medication lisinopril dropped to less than $5 for a 30-day supply after five manufacturers entered the market. That’s a 95% drop from the brand price. Similar stories happened with antibiotics like amoxicillin and cholesterol drugs like atorvastatin. These are the drugs that work the way they’re supposed to-lots of makers, low prices.

The Dark Side: When Prices Skyrocket Instead

But not all generics follow this pattern. In fact, about 15% of generic drugs experience wild price swings-some jumping over 20% in a single year. And in extreme cases, prices have exploded. Generic nitrofurantoin, used for urinary tract infections, went from $12 to over $160 in five years. Levothyroxine, a thyroid medication taken by millions, saw its price drop 87% over the same period-while another version of the same drug jumped 200%.

What’s behind this? Usually, it’s a lack of competition. If only one or two companies make a drug, they can raise prices without fear of losing customers. The FDA found that 78% of price hikes over 100% happened in markets with three or fewer manufacturers. In 2013-2014, nearly 1 in 12 generic prescriptions saw a price surge between 100% and 500%. That’s not a glitch-it’s the market structure.

Why Do Some Generics Have So Few Makers?

It’s not that no one wants to make them. It’s that making generic drugs is harder-and riskier-than it looks. The FDA requires every batch to meet strict quality standards. If a factory gets flagged for contamination or poor record-keeping, production stops. That’s happened in India and China, where most generic drugs are made. When a supplier gets shut down, the drug vanishes from shelves. And when it comes back, the price is often double.

There’s also consolidation. In 2013, about 150 companies made generic drugs in the U.S. By 2018, that number dropped to 80. Today, the top five companies control more than half of the market. That means fewer players to keep prices in check. When one of them decides to raise prices, others follow-because they know you have nowhere else to turn.

What’s Happening Right Now? 2022 to 2025

Looking at the last few years, the overall trend for generic prices looks calm: increases of 1-5% per year. But that’s an average. Behind it, chaos.

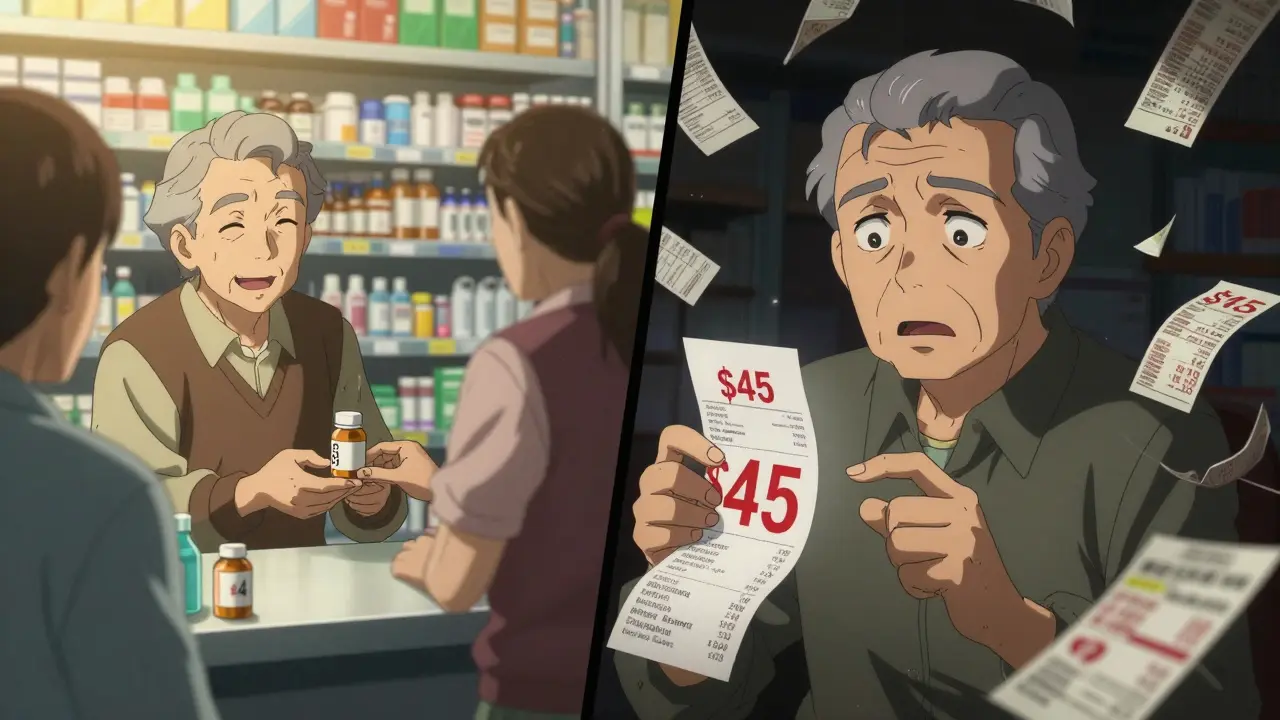

In 2022-2023, about 40 generic drugs saw price increases averaging 39%. One of them? Generic lisinopril. At Walmart, the cash price jumped from $4 to $45 in 18 months. That’s not a typo. Patients on fixed incomes suddenly had to choose between their medication and groceries.

Medicare beneficiaries reported that 37% of them skipped doses or cut pills in half because of cost. Independent pharmacies, already thin on margins, had to absorb $3.75 per prescription in losses on 20% of their generic inventory. Some generics flipped from profitable to loss leaders in weeks.

Meanwhile, the Inflation Reduction Act introduced new rules for brand-name drugs, forcing manufacturers to pay rebates if prices rose too fast. But for generics? Nothing. They’re still at the mercy of the market. The FDA’s own data shows that 40% of approved generics have three or fewer manufacturers-making them vulnerable to the next price spike.

Who Gets Hurt the Most?

It’s not just the elderly or low-income patients. It’s anyone taking a generic drug that’s made by only one or two companies. Cardiovascular drugs, thyroid meds, seizure medications, and some antidepressants are especially risky. These are drugs people take every day, for life. A $10 jump per month adds up to $120 a year. For someone on Social Security, that’s a rent payment.

GoodRx users report saving an average of $112 per prescription compared to cash prices at big pharmacies. But that only helps if you know to check. Many people don’t. They walk into the pharmacy, get handed the same pill they’ve always taken, and pay whatever they’re told. Then they get a bill they didn’t expect.

What Can You Do?

You can’t control who makes your drug or how much they charge. But you can control what you pay.

- Always check GoodRx, SingleCare, or RxSaver before filling a prescription. Prices vary wildly between pharmacies-even within the same chain.

- Ask your pharmacist if there’s a different generic version available. Sometimes the same drug is made by another company at a lower price.

- If your price jumps suddenly, call your doctor. They might be able to switch you to a different generic or a similar drug with more competition.

- Use mail-order pharmacies or 90-day supplies. They often have better pricing, especially for chronic medications.

- Sign up for patient assistance programs. Some manufacturers offer discounts even on generics if you qualify.

The Bigger Picture: Is This Fixable?

Regulators are starting to pay attention. The FTC has 12 active investigations into price gouging in generic drug markets. The FDA plans to speed up approvals for drugs with few makers. Medicaid now requires manufacturers to offer the same low price to all buyers, which should prevent some spikes.

But the system is still fragile. A single factory shutdown in India can cause a shortage that lasts months. A small company going out of business can leave a drug with only one maker. And when that happens, prices don’t just go up-they explode.

The promise of generics was simple: same medicine, lower cost. For most drugs, that’s still true. But for too many, that promise has been broken. The problem isn’t the pills. It’s the market. And until more companies are allowed to compete fairly, the next price spike could be just around the corner.

Why do generic drug prices go up even though they’re supposed to be cheaper?

Generic drugs are cheaper on average, but prices can spike when only one or two companies make a drug. Without competition, manufacturers can raise prices without losing customers. This often happens after a competitor exits the market or if manufacturing issues cause shortages. The FDA found that 78% of price hikes over 100% occur in markets with three or fewer manufacturers.

Which generic drugs are most likely to have price spikes?

Drugs with few manufacturers-especially cardiovascular medications, thyroid hormones, seizure treatments, and some antibiotics-are most at risk. For example, generic nitrofurantoin and certain versions of levothyroxine saw price increases over 1,000% in recent years. These are often older, low-margin drugs that manufacturers only make if there’s little competition.

How can I find the lowest price for my generic medication?

Use price-comparison tools like GoodRx, SingleCare, or RxSaver. Prices can vary by hundreds of dollars between pharmacies-even within the same chain. Always ask your pharmacist if another generic version is available. Sometimes the same drug is made by a different company at a lower cost. Mail-order pharmacies and 90-day supplies often offer better deals too.

Why don’t insurance plans cover the lowest generic price?

Insurance plans often use Average Wholesale Price (AWP) or a fixed copay structure that doesn’t reflect the real cost of the drug. Many pharmacies pay less than what insurance pays, but patients still get billed the full copay. This is especially true for small, independent pharmacies that struggle to keep up with rapid price changes. The gap between what pharmacies pay and what insurers reimburse can be as high as 22%.

Are generic drugs still safe if their prices keep changing?

Yes. The FDA requires all generic drugs to meet the same safety and effectiveness standards as brand-name drugs. Price changes don’t affect quality. A $5 pill and a $50 pill of the same generic drug contain the same active ingredient and work the same way. The difference is in the market-not the medicine.

What’s being done to stop generic drug price gouging?

The FTC has 12 active investigations into price spikes in markets with few manufacturers. The FDA is speeding up approvals for drugs with limited competition. Medicaid now requires manufacturers to offer the same low price to all buyers. But enforcement is slow, and the market remains vulnerable. Experts say real change will only come if more companies are allowed to enter-and stay-in the market.

What’s Next?

If you take a generic drug, check your prescription cost every few months. If it’s gone up suddenly, don’t assume it’s normal. Ask questions. Shop around. Talk to your pharmacist. You’re not alone-millions are in the same boat. And while big policy changes take time, your next step is simple: know your price, know your options, and don’t pay more than you have to.

The structural inefficiencies in the generic drug supply chain are a textbook case of market failure masked as competition. When you have oligopolistic consolidation-where the top five firms control >50% of volume-you’re not seeing price discovery; you’re seeing tacit collusion. The FDA’s approval latency for niche generics, coupled with GMP non-compliance risks in global manufacturing hubs, creates artificial scarcity. This isn’t capitalism-it’s rent-seeking disguised as pharmaceutical distribution.