Anti-Androgen Comparison Tool

Medication Comparison Tool

Select your priorities to see which anti-androgen might be most suitable for your prostate cancer treatment.

Quick Takeaways

- Flutamide (Eulexin) is an older first‑generation anti‑androgen; it blocks testosterone receptors but requires high doses.

- Second‑generation drugs like bicalutamide, enzalutamide and apalutamide offer stronger receptor binding and fewer liver concerns.

- Nilutamide is similar to flutamide in potency but has unique visual side‑effects that limit its use.

- When anti‑androgens are paired with hormone‑lowering therapy (GnRH agonists or surgical castration), overall cancer control improves.

- Cost and side‑effect profile often decide which agent is best for a given patient.

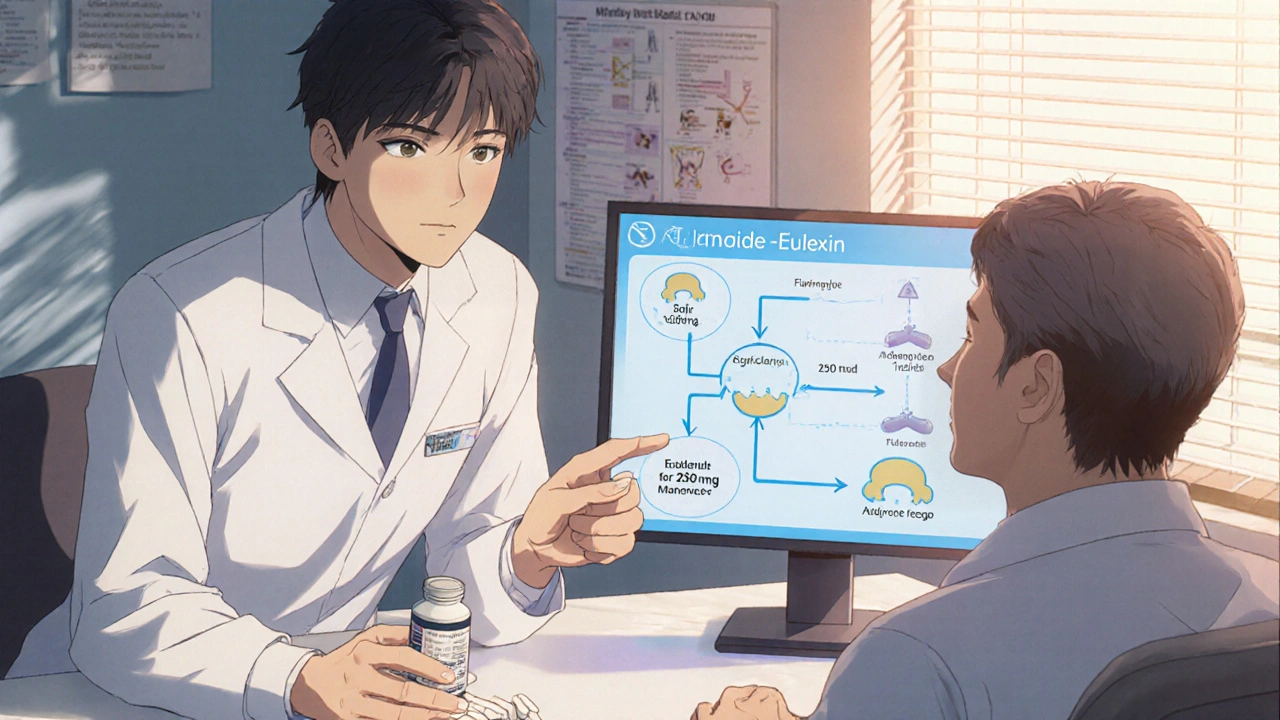

What Is Flutamide (Eulexin)?

Flutamide is a non‑steroidal, first‑generation anti‑androgen marketed under the brand name Eulexin. It works by competitively inhibiting the androgen receptor, preventing testosterone and dihydrotestosterone from stimulating prostate cancer cells. Approved by the FDA in 1989, flutamide is typically taken in 250 mg tablets three times daily, with total daily doses ranging from 750 mg to 1 g.

Because flutamide does not lower circulating testosterone, it is almost always combined with a gonadotropin‑releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist such as leuprolide or with surgical castration to achieve full androgen deprivation. Its main drawbacks are a relatively high incidence of liver‑function abnormalities and the need for multiple daily doses, which can affect adherence.

How Anti‑Androgens Work in Prostate Cancer

The androgen receptor (AR) drives prostate‑cell growth. By blocking AR binding, anti‑androgens halt tumor proliferation. First‑generation agents (flutamide, nilutamide) bind the receptor with modest affinity, while second‑generation drugs (bicalutamide, enzalutamide, apalutamide) have been chemically refined to achieve stronger blockade and to prevent receptor translocation into the nucleus.

Adding a GnRH agonist or performing bilateral orchiectomy reduces the testosterone pool, creating a two‑pronged attack: less hormone available + the receptor blocked. This combination is called combined androgen blockade (CAB).

Key Alternatives to Flutamide

Below are the most commonly prescribed anti‑androgens that clinicians consider when flutamide isn’t ideal.

Bicalutamide (Casodex)

Bicalutamide is a second‑generation non‑steroidal anti‑androgen introduced in 1995. It binds the AR with roughly ten times the affinity of flutamide and is taken once daily (usually 50 mg). Because it has a lower risk of hepatic toxicity, many doctors favor bicalutamide as the first‐line oral anti‑androgen.

Nilutamide (Nilandron)

Nilutamide shares a similar mechanism to flutamide but is more potent, allowing lower doses (300 mg once daily). Its biggest limitation is a distinctive side‑effect profile that includes visual disturbances and nausea, making it a less common choice today.

Enzalutamide (Xtandi)

Enzalutamide is a third‑generation anti‑androgen approved in 2012 for metastatic castration‑resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). It not only blocks the AR but also prevents its nuclear translocation and DNA binding. The standard dose is 160 mg once daily, and it’s known for a favorable progression‑free survival benefit, though fatigue and seizures are reported in a small subset.

Apalutamide (Erleada)

Apalutamide, approved in 2018, is structurally similar to enzalutamide but offers a slightly better safety profile in non‑metastatic disease. It’s taken as 240 mg daily and has shown impressive metastasis‑free survival in clinical trials.

GnRH Agonist Example: Leuprolide

Leuprolide doesn’t block the AR directly; instead, it suppresses the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑gonadal axis, dropping testosterone to castrate levels. When paired with any oral anti‑androgen, it creates the most complete hormonal blockade.

Surgical Castration

Orchiectomy eliminates testicular testosterone production permanently. It’s inexpensive and eliminates the need for monthly injections, but the irreversible nature makes it a last‑resort option for many patients.

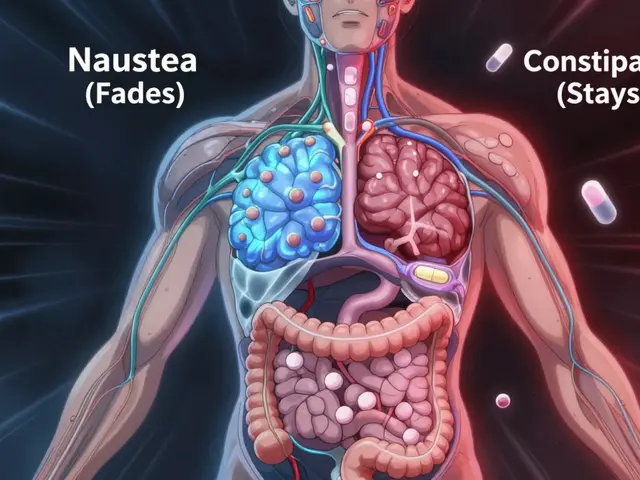

Side‑Effect Comparison

Understanding tolerability is key. Below is a concise snapshot of the most clinically relevant adverse events for each drug.

| Drug | Common Toxicities | Serious Risks | Typical Dose | Cost (US$ per month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flutamide | Gastro‑intestinal upset, hot flashes | Liver enzyme elevation (up to 10% severe), hepatotoxicity | 750 mg-1 g daily (3×250 mg) | ≈ $30 |

| Bicalutamide | Gynecomastia, breast pain | Rare severe liver injury | 50 mg daily | ≈ $150 |

| Nilutamide | Nausea, visual impairment (blurred vision, night blindness) | Severe retinal toxicity in <5% of patients | 300 mg daily | ≈ $120 |

| Enzalutamide | Fatigue, hypertension | Seizures (≈ 1%); drug‑drug interactions via CYP2C8 | 160 mg daily | ≈ $4,800 |

| Apalutamide | Rash, diarrhea | Seizures (≈ 0.5%); higher skin toxicity | 240 mg daily | ≈ $5,200 |

Choosing the Right Anti‑Androgen: Decision Factors

When you compare flutamide with its rivals, ask yourself these practical questions:

- What is the disease stage? Early‑stage patients on CAB often do well with bicalutamide; advanced mCRPC may need enzalutamide or apalutamide.

- How critical is liver safety? If a patient has pre‑existing hepatic impairment, avoid flutamide and nilutamide.

- Is cost a barrier? Generic flutamide remains the cheapest oral option, but insurance coverage for newer agents can offset high list prices.

- Are adherence concerns present? Once‑daily dosing of bicalutamide, enzalutamide, or apalutamide simplifies regimens compared with flutamide’s three‑times‑daily schedule.

- Any comorbidities? Patients with seizure history should steer clear of enzalutamide and apalutamide.

After weighing these variables, many clinicians start with bicalutamide for its balance of efficacy and tolerability. They reserve flutamide for patients who cannot afford newer agents and have normal liver tests.

Real‑World Example: Switching from Flutamide to Bicalutamide

Mr. J., a 68‑year‑old with locally advanced prostate cancer, started on flutamide + leuprolide two years ago. Routine labs recently showed ALT/AST elevations (3× upper limit). His oncologist discussed alternatives, and they switched to bicalutamide 50 mg daily while continuing leuprolide. Within four weeks, liver enzymes normalized, and Mr. J. reported fewer hot flashes because of the reduced pill burden. This case illustrates how a relatively cheap switch can improve safety and quality of life.

Summary of Comparative Strengths

| Drug | Receptor Affinity | Convenience | Safety Highlights | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flutamide | Low | 3× daily dosing | Higher hepatotoxicity risk | Budget‑constrained CAB |

| Bicalutamide | Medium‑high | Once daily | Low liver risk, gynecomastia common | Standard oral anti‑androgen |

| Nilutamide | Medium‑high | Once daily | Visual toxicity | Rarely used today |

| Enzalutamide | Very high | Once daily | Seizure risk, drug interactions | mCRPC, high‑risk disease |

| Apalutamide | Very high | Once daily | Skin rash, low seizure rate | Non‑metastatic high‑risk |

Bottom Line: When to Choose Flutamide (Eulexin)

If you need the most affordable oral anti‑androgen, have normal liver function, and can manage three daily tablets, flutamide remains a viable option. However, for most patients today, the Flutamide alternatives-especially bicalutamide-offer a smoother safety profile, simpler dosing, and comparable efficacy when combined with hormonal suppression.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can flutamide be used alone without a GnRH agonist?

No. Flutamide blocks the receptor but does not lower testosterone levels, so it must be paired with a GnRH agonist (e.g., leuprolide) or surgical castration for effective androgen deprivation.

Is bicalutamide safer for patients with liver disease?

Yes. Bicalutamide has a much lower incidence of severe hepatotoxicity compared with flutamide or nilutamide, making it the preferred choice when hepatic function is a concern.

What are the main reasons to pick enzalutamide over bicalutamide?

Enzalutamide provides stronger AR blockade, works in patients who have progressed on earlier anti‑androgens, and improves overall survival in metastatic castration‑resistant disease. It’s chosen when disease is advanced or resistant to first‑generation agents.

How does nilutamide differ from flutamide in terms of dosing?

Nilutamide is more potent, so it’s given as a single 300 mg tablet daily, whereas flutamide requires three 250 mg tablets a day.

Are there any diet or lifestyle restrictions while taking flutamide?

Patients should avoid excessive alcohol and hepatotoxic substances, monitor liver enzymes regularly, and report any signs of jaundice promptly.

Next Steps for Patients and Providers

1. Review the patient’s liver function tests, seizure history, and financial situation.

2. Choose the anti‑androgen that best balances efficacy with tolerability.

3. Initiate combined androgen blockade with a GnRH agonist or orchiectomy.

4. Schedule follow‑up labs (LFTs, PSA) at 4‑6 week intervals.

5. Adjust therapy promptly if adverse events emerge.

By following this roadmap, clinicians can personalize prostate‑cancer treatment, ensuring patients receive the most appropriate anti‑androgen-whether that’s the classic flutamide or a newer, more potent alternative.

When you look at the landscape of anti‑androgen therapy for prostate cancer, the first thing to notice is that the older agents like flutamide were really groundbreaking for their time, even though they demand three times‑daily dosing which can be a compliance nightmare. Flutamide’s mechanism of competitively blocking the androgen receptor is straightforward, but the drug’s relatively low binding affinity means you need higher plasma concentrations to achieve the same blockade you get from newer molecules. This pharmacologic fact translates into the need for a total daily dose of 750 mg to 1 g, which isn’t ideal for many patients who already struggle with the side‑effects of hormone suppression. The liver toxicity profile of flutamide is another major consideration; clinicians routinely monitor transaminases because elevations can occur in up to ten percent of patients and occasionally progress to severe injury. By contrast, bicalutamide, introduced in the mid‑1990s, binds the receptor with roughly ten times the affinity of flutamide and can be given as a single 50‑mg tablet each day, dramatically simplifying the regimen. Moreover, bicalutamide’s lower risk of hepatotoxicity makes it a more attractive first‑line oral agent in most treatment algorithms. Nilutamide sits somewhere in between: it’s more potent than flutamide, so you only need 300 mg once daily, but it brings a quirky side‑effect profile that includes visual disturbances and nausea, limiting its popularity. Enzalutamide and apalutamide, the third‑generation anti‑androgens, push the envelope further by not only blocking the receptor but also preventing nuclear translocation and DNA binding, which translates into superior progression‑free survival in several phase‑III trials. The dosing convenience of enzalutamide (160 mg once daily) and apalutamide (240 mg once daily) also means you’re not fragmenting the day with multiple pills, a real quality‑of‑life win for patients on chronic therapy. Cost, however, is a double‑edged sword: while flutamide can be sourced for as little as thirty dollars a month, the newer agents can run into the high‑hundreds, creating access barriers for some health systems. In practice, many oncologists start with a GnRH agonist like leuprolide to achieve castrate testosterone levels and then add the oral anti‑androgen that best matches the patient’s comorbidities and financial situation. This combined androgen blockade strategy has repeatedly shown improved overall survival compared with hormone therapy alone, regardless of which anti‑androgen you choose. When you factor in patient preference, liver function, visual health, and budget, the decision matrix becomes a nuanced balancing act rather than a simple “old versus new” dichotomy. Ultimately, the goal is to maintain androgen deprivation while minimizing toxicity, and the expanding armamentarium of anti‑androgens gives us the flexibility to tailor therapy in a way that was unimaginable a decade ago. So, while flutamide remains a viable option in resource‑limited settings, most clinicians now reserve it for specific scenarios where cost constraints outweigh the convenience and safety benefits of the newer agents. Each patient’s journey is unique, and the art of oncology lies in matching the right drug to the right individual.