Fertility Chemical Exposure Risk Calculator

Your Exposure Profile

Risk Assessment

Your personalized recommendations will appear here based on your risk profile.

Key Chemicals Affecting Fertility

Reduced sperm motility, lower ovarian reserve

Hormonal imbalances, altered ovulation timing

Impaired steroidogenesis, increased miscarriage risk

Disruption of hormone axis, DNA damage in gametes

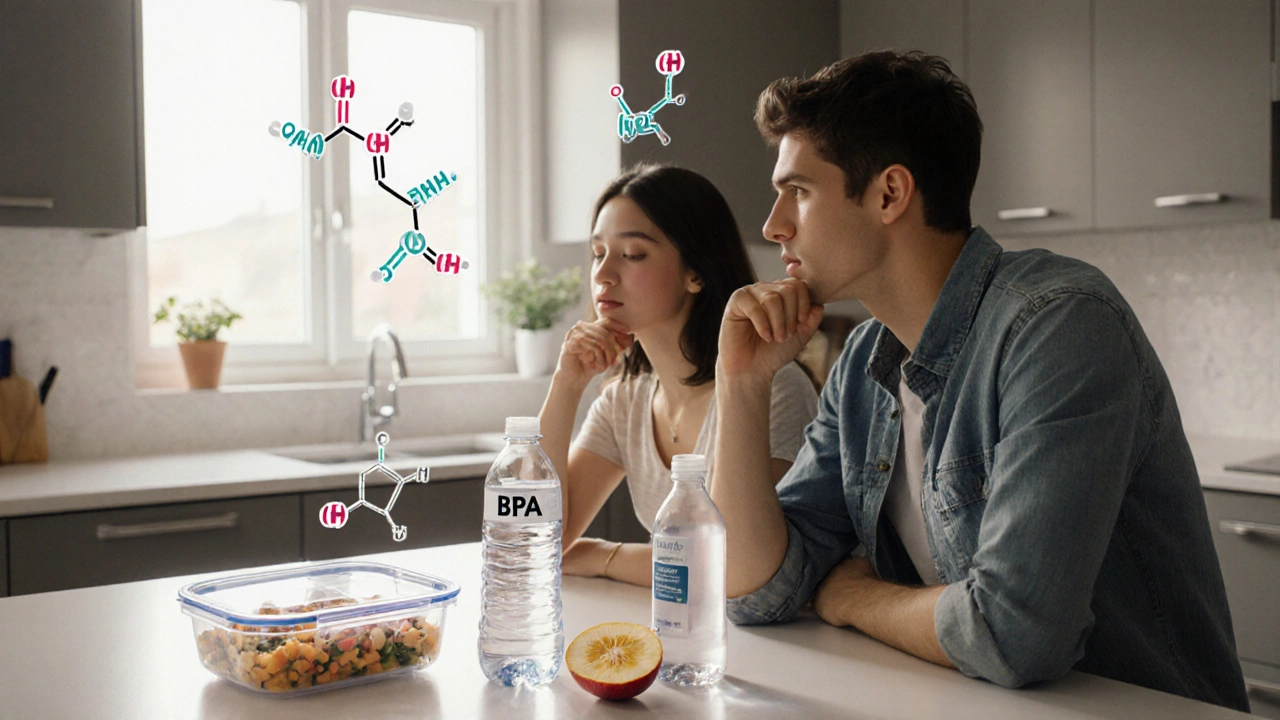

When trying to start or expand a family, the last thing you want is an invisible threat that quietly harms fertility. Scientific research increasingly links everyday chemicals to reduced sperm quality, altered menstrual cycles, and lower pregnancy rates. Knowing which substances to steer clear of can make a measurable difference for both partners.

Quick Takeaways

- Endocrine‑disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are the biggest culprits; they mimic or block hormones essential for reproduction.

- Common sources include plastic containers (phthalates, BPA), personal‑care products (parabens), and certain foods (pesticide residues).

- Reduce exposure by choosing glass or stainless‑steel containers, opting for fragrance‑free cosmetics, and buying organic produce when possible.

- Indoor air quality matters - replace older foam furniture and avoid smoking indoors.

- Consult a reproductive specialist if you suspect high chemical exposure; testing can guide personalized mitigation.

Understanding How Chemicals Impact Reproductive Health

Chemical exposure affecting fertility is a public‑health concern that involves any external substance that interferes with the hormonal pathways controlling gamete production, implantation, or early embryonic development. The mechanisms are often subtle: chemicals can bind to estrogen or androgen receptors, disrupt the synthesis of luteinizing hormone, or generate oxidative stress that damages DNA in sperm and eggs.

Because the reproductive system is highly regulated by hormones, even low‑level, chronic exposure can accumulate enough effect to lower conception chances. Studies from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) estimate that up to 30% of unexplained infertility cases have a chemical component.

Major Fertility‑Harming Chemicals You Should Know

The following list covers the most studied groups, their typical sources, and the specific ways they interfere with reproduction.

Endocrine‑Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs)

EDCs are a broad class that includes many of the chemicals detailed below. They share the ability to mimic, block, or alter hormone signaling.

Phthalates

Used to soften PVC plastics, phthalates are found in shower curtains, food‑wrap films, and some personal‑care products. Research links high urinary phthalate levels to reduced sperm motility and lower antral follicle counts in women.

Bisphenol A (BPA)

BPA is the polymerizer in polycarbonate bottles and epoxy food‑can linings. It binds weakly to estrogen receptors, creating a hormonal “noise” that disrupts the feedback loop controlling ovulation and spermatogenesis.

Pesticides (organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids)

Residual pesticides on fruits, vegetables, and even indoor dust can inhibit the activity of enzymes essential for steroid hormone production. Epidemiological data link occupational pesticide exposure to higher miscarriage rates.

Heavy Metals (lead, mercury, cadmium)

These metals accumulate in bone, kidney, and reproductive tissues. Lead interferes with the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑gonadal axis, while mercury generates free radicals that damage sperm DNA.

Flame Retardants (PBDEs)

PBDEs are applied to furniture foams and electronics. They act as thyroid hormone antagonists, and animal studies show reduced litter sizes after chronic exposure.

Parabens

Common preservatives in shampoos, lotions, and cosmetics. Parabens can weakly activate estrogen receptors, potentially altering the timing of ovulation.

How Exposure Happens: Common Pathways

- Ingestion: Consuming contaminated food or water.

- Inhalation: Breathing indoor air with volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or outdoor pollutants like PM2.5.

- Dermal absorption: Contact with cosmetics, hand sanitizers, or treated fabrics.

Because most people encounter multiple routes daily, the cumulative burden can be significant even if each individual source seems harmless.

Practical Steps to Reduce Exposure at Home

- Swap plastic food containers for glass or stainless steel. Choose BPA‑free labeling only when you also verify the product is free of phthalates.

- Buy fresh or frozen produce with minimal packaging. Wash fruits and vegetables with a solution of vinegar and water to strip pesticide residues.

- Use fragrance‑free, paraben‑free personal‑care items. Look for “hypoallergenic” or “unscented” labels.

- Replace older foam cushions and mattresses-these often contain PBDEs. Opt for natural latex or certified low‑emission fabrics.

- Filter tap water with activated carbon or reverse‑osmosis systems to remove lead, mercury, and residual chlorine.

- Ventilate indoor spaces regularly. Open windows for at least 15 minutes each day to dilute indoor VOC concentrations.

Workplace and Environmental Considerations

If you work in manufacturing, agriculture, or labs, you may face higher levels of solvents, pesticides, or heavy metals. Use proper personal protective equipment (PPE) and advocate for regular air‑monitoring programs. For urban residents, consider app‑based air‑quality trackers and plan outdoor activities when PM2.5 levels are low.

Food and Water: What to Look For

Choosing the right foods can both cut chemical intake and boost reproductive health. Prioritize:

- Organic dairy and meat-reduces exposure to hormone‑disrupting growth promoters.

- Wild‑caught fish with low mercury levels (e.g., salmon, sardines) - provides omega‑3s that counteract oxidative stress.

- Whole grains and legumes - fibre helps the body eliminate stored toxins.

Avoid canned soups and ready‑meals that rely on BPA‑lined cans, and limit processed meats that often contain phthalate‑based packaging.

Comparison of Common Fertility‑Harming Chemicals

| Chemical | Typical Sources | Impact on Reproductive Health | Risk Level (based on average exposure) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phthalates | Plastic wraps, shower curtains, personal‑care products | Reduced sperm motility, lower ovarian reserve | High |

| BPA | Polycarbonate bottles, canned‑food linings | Hormonal imbalances, altered ovulation timing | High |

| Pesticides | Residues on produce, indoor dust | Impaired steroidogenesis, increased miscarriage risk | Medium‑High |

| Heavy Metals (Lead, Mercury) | Old paint, contaminated water, certain fish | Disruption of hormone axis, DNA damage in gametes | Medium |

| Flame Retardants (PBDEs) | Furniture foam, electronics | Thyroid hormone antagonism, reduced litter size (animal models) | Medium |

| Parabens | Cosmetics, lotions, sunscreens | Weak estrogenic activity, possible ovulatory disruption | Low‑Medium |

When to Seek Professional Help

If you and your partner have been trying to conceive for over a year (or six months if the woman is over 35) and suspect chemical exposure, a reproductive endocrinologist can order blood and urine tests to quantify specific EDCs. Results guide personalized detox plans, dietary adjustments, and, if needed, medical interventions such as antioxidant supplementation.

Bottom Line

Everyday chemicals can stealthily undermine reproductive potential, but targeted actions-choosing safer containers, cleaning food, improving indoor air, and opting for organic produce-significantly lower the risk. Combine these steps with regular medical monitoring, and you give your body the best shot at a healthy pregnancy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can occasional exposure to BPA still affect fertility?

Yes. Even intermittent BPA intake can create hormonal fluctuations that interfere with ovulation and sperm quality. Consistent avoidance-especially during the pre‑conception window-offers measurable benefits.

Are all plastics equally risky?

No. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles used for water are generally safer than polyvinyl chloride (PVC) containers, which often contain phthalates. Look for #1 or #2 recycling codes to choose lower‑risk plastics.

Does drinking filtered water remove all reproductive toxins?

A high‑quality carbon or reverse‑osmosis filter removes most heavy metals, BPA, and certain pesticide residues, but it won’t eliminate volatile organic compounds that might be present in the air. Combining water filtration with indoor‑air ventilation gives the best overall protection.

Is there a safe level of phthalate exposure?

Regulatory agencies set “acceptable daily intake” levels, but recent studies suggest even low‑level exposure can affect sensitive reproductive endpoints. Minimizing any non‑essential phthalate contact is the most prudent approach.

Can antioxidant supplements counteract chemical damage?

Antioxidants like vitamin C, vitamin E, and coenzyme Q10 can reduce oxidative stress caused by heavy metals and some pesticides, but they don’t eliminate the underlying hormonal disruption. Use them as a complement to exposure reduction, not a replacement.

While the article outlines the major culprits-phthalates, BPA, pesticides, and heavy metals-it neglects to mention the cumulative effect of low‑level exposure over decades. Epidemiological studies have consistently shown a dose‑response relationship, even at concentrations previously deemed safe. Moreover, the risk calculator oversimplifies occupational exposure by assigning a single integer value, ignoring nuanced differences between industries. A more rigorous approach would stratify exposure by duration, protective equipment usage, and biomonitoring data. Finally, policymakers should consider stricter regulations on endocrine‑disrupting compounds, not merely consumer advisories.